Cosina-Voigtländer’s Bessaflex TM is one of my favorite cameras. It’s an incredibly beautiful and refined camera that was discontinued (2007) as suddenly as it was put on the market (2003). There are but a handful of in-depth articles on it online, and I felt compelled to publish my thoughts on it.

Voigtländer (pronounced ‘voihkt-lehnder’) is a loaded name in photography. Founded in 1756, it is essentially the oldest name in camera history. Its tradition of innovation is rich, including being the first to introduce the photographic zoom lens as well as the first 35mm film camera with built-in flash. Like many aging titans it was overtaken by more eager young companies and eventually closed its doors, the brand name being sold and used between various companies before end up at Cosina, a Japanese camera company.

Today, Cosina does the Voigtländer name and its historical significance justice: it produces a series of high-quality mechanical film rangefinder cameras branded with the Voigtländer name called ‘Bessa’, as well as a series of lenses for the Leica M-mount that almost rival the famous German camera maker’s own in quality and easily beat them in price. But in 2003, something new came out of Cosina-Voigtländer: A curious experiment; a mechanical universal thread mount SLR camera called the Bessaflex TM.

Taking stylistic inspiration from the Bessa camera and older Voigtländer SLRs, the Bessaflex is an sleek, beautifully designed camera made for an older, practically extinct thread lens mount called M42 – hence the ‘TM’ for Thread Mount. At some point this universal standard thread mount was surpassed by electronic contact bayonet mounts like Canon’s EF mount, allowing for modern comforts like autofocus, electronic and automatic aperture control, and more.

Personally, I find these ‘modern comforts’ of photography more of a hindrance than a contribution to photography. When I first got a Canon Digital Rebel with accompanying beginner lens, I was often frustrated with its lack of intelligence in picking what to focus on. I had very little knowledge of the joy one could find in adjusting the lens manually to focus on exactly what you want to see. Once I found out about this everything changed. Suddenly, there was no struggle with the middle-man that fought your eye and what you wanted to capture. My hands controlled the image in a direct way, almost like a brush on a canvas. It may sound strange, but I felt much closer to what I was photographing.

I soon found that there was a large number of photographers that shared this sentiment. I started building a collection of fantastic old lenses with a history of their own that had great optical qualities and were a delight to use and feel: they often equalled or surpassed expensive modern electronic lenses when adapted to my modern-day Canon 5D Mark II SLR camera. However, I’d been struck with an infatuation that would not stop at the lens. The adapted lenses on the 5D Mark II made shooting feel like a cobbled-together solution of the new and the old, a heavy metal-and-glass conflict in my hands that could only be settled with one solution: I had to get an older camera that these lenses were designed for. The continued love for this style of shooting I experienced is what motivated Cosina to make the Bessaflex TM. I eventually solved my conflict by switching from a digital camera to an older Fujica ST650N 35mm SLR – which eventually led to me ultimately purchasing a Bessaflex.

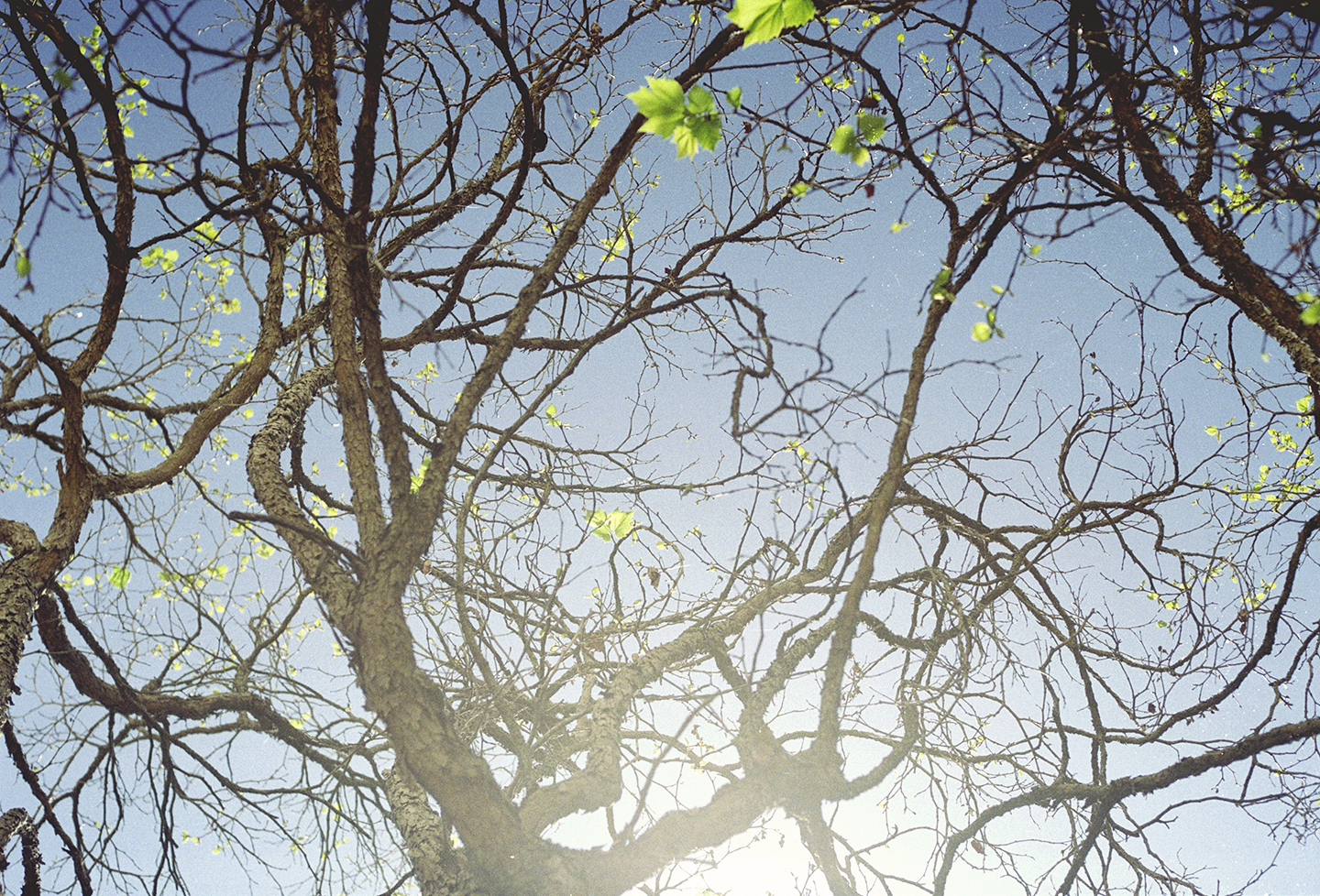

A note on lenses: M42 thread mount lenses are abundant and cheap. From former Soviet Union lenses based on Zeiss designs to proper Carl Zeiss lenses, there are numerous great brands to pick from: Carl Zeiss (Jena), Chinon, Contax, Enna, Exaktar, Fujinon, Pentax, Porst, Revue, Sigma, Tamron, Tokina, Vivitar, Voigtländer, Yashinon, and more. All samples I posted with this article were taken with M42 lenses or M39 lenses adapted to the M42 screw thread.

It’s a cliché, but I find it hard to overstate how much this change helped me improve as a photographer. Every frame of the rolls out of my Fujica were objectively better photos, and the qualities of the old lenses came out much better. They were simply not optimized for the electronic imaging sensors of today. Their images – while beautiful – lacked the emotional quality that came from shots from the film camera. And then there was the feel: in my hands, the Fujica with my old lenses worked as it was supposed to. I composed and focused the image in a split-screen prism with my hands, set my aperture, chose the right exposure time and took the image. Eventually, however, the Fujica met its end as I ran frantically though an airport to make a connection to Tampa and a lug on the camera strap holding it on my neck gave out, the camera smashing into the ground and spreading little metal parts everywhere. In my hurry, I couldn’t gather all the parts and narrowly made the connecting flight. While I rigged the thing back together and it took photos okay, it was time for me to look for a new screw-mount film camera – preferably a small step up from the Fujica with its dated 1/700th maximum exposure time and ultra-loud shutter.

The rest is history. A lot of research eventually led me to this little discontinued wonder of the camera world. By all measures, the Bessaflex TM is a modern film camera. Its mechanical Copal shutter goes up to 1/2000th of a second and works without battery power, it has extremely accurate and precise light metering, is manufactured to very tight tolerances and even has a nice little film preview window on its back. Yet it is styled after the cream of the crop of the older German cameras, with the silver Bessaflex looking particularly similar to the Topcon Super D. It’s strong, yet light and small. Modern, yet classical and inconspicuous. And best of all, it has a huge – and supposedly the brightest – viewfinder out of all M42 mount cameras. I was in love.

Design

The Bessaflex TM came in two editions: a black version, which was initially released, and the silver version shown here which appears to be styled after the Topcon Super RE camera, a beautiful piece of 1960s Japanese camera innovation. Both lack a flash ‘hot shoe’ on the top of the viewfinder, which enhances their clean, no-frills appearance. The silver version is made from an anodized light metal – I can’t find the exact type of metal, though it feels like a magnesium alloy. The front of the camera is only decorated with a simple ‘Bessaflex’ engraved into the pentaprism housing and a ‘TM’ engraved above the lens mount to the right. The black leatherette, which wraps the camera all the way around, is also interrupted by a small self-timer lever to the left of the lens mount. Overall, the camera has nice, simple, square lines which are slightly rounded to still feel comfortable in the hand or when pressed up against your face or sides.

The buttons and knobs look similar to those seen on the Bessa R rangefinders, the buttons having a pleasant convex shape and the textured ridged knobs for shutter speed setting and film ISO speed are very refined. The silver version is accentuated with a small, leatherette-covered patch on the pentaprism housing and a plastic grip on end the rapid advance lever – a detail I have never been a fan of. I vastly prefer all-metal levers on cameras.

It has a typical Cosina style hinged rear door. If you’ve used a Bessa, Zeiss Ikon, or any other camera by them you know how they look. The inside is clean and well laid out. The whole looks fairly uninterrupted: only a few small seams run across the metal frame of the camera.

The back is cutely adorned with a small piece of engraved text that reads ‘VOIGTLÄNDER – GERMANY – Since 1756’.

Feel and Usability

While beautiful, the Bessaflex is no camera to keep on a shelf. This camera was made to be used.

When you first hold a Bessaflex, you get two immediate impressions. The first is how well-built it is, as the entire camera feels very tightly made and comfortable. As far as film SLR bodies go, the Bessaflex is among the best in class, rivaling even the feel of most film rangefinders (though, not quite up to the level Leica / Zeiss Ikon). Its leather(ette?) is the best I’ve ever felt on an SLR camera. The second is how light it is. The Bessaflex is a very light camera – it seems Cosina-Voigtländer was mindful, however, in ensuring the small weight of the camera would not make it feel any less dense or well-built. It’s comparable to when I first held an iPhone 5 after having used an iPhone 4 / 4S for two years; one experiences it as feeling ‘oddly light’, but the ‘odd’ part of the sensation quickly wears off. For extra comfort, the Bessaflex has an excellent, rubbery textured extrusion on the rear that greatly enhances the comfort of holding it.

The shooting experience is superb. From the very soft, leafy shutter sound to the extremely bright viewfinder and the quick yet solid feel of the rewind lever, it’s unlike any film SLR I have used. It’s extremely pleasant and tactile yet completely gets out of your way when you shoot. The back is comfortable if you are one of those people that presses the camera firmly into their face, the button has exactly the right amount of resistance and the rapid advance lever makes the best kind of whirring, clicky action when you use it. You have to use it to truly appreciate it.

Is it all perfect? No. My main quibble with the camera is the metering switch, located next to the lens on the right-hand side (if you are using the camera, to the left of the lens). It took me some getting used to; it’s a (by comparison) somewhat flimsy feeling mechanism that you can push upward to activate the TTL metering, or push a bit more firmly to lock into place for continuous metering while you adjust other settings. This switch also engages a cam in the lens mount to push in the stop-down metering pin for more modern M42 lenses; so far, it has worked with most of the ones I have tested.

Regardless, the metering switch is somewhat intuitive and works fairly well, but isn’t as quick or ergonomic as the Fujica or Nikon methods. Once you are used to it, it works fine. The metering switch reverts to its off state after you shoot a frame, ensuring you don’t run down the battery inadvertently after putting the camera away.

Speaking of battery: the Bessaflex TM is completely mechanical. If you do end up with a dead battery, the entire camera operates perfectly. There is no on/off switch or circuitry that will die with a bit of moisture: the shutter, film advance and other critical camera components do not require any electricity whatsoever. This is a fantastic feature, and extremely rare in modern cameras.

The Bessaflex has TTL (Through-the-Lens) LED metering indicators in the viewfinder on its left side: a + indicates overexposure, a solid dot indicates correct exposure, and a – indicates underexposure. Simple enough. It can show a 1/2 stop under- or overexposure by showing both the dot and a +/-, similar to Leica’s in-viewfinder metering display. It’s simple and does the job, unless you vastly prefer moving-needle metering.

Specs

– The Bessaflex takes two commonly available S76 batteries.

– The Bessaflex comes with a transparent window on the rear for reviewing the film type and speed – a nice detail.

– The viewfinder has close to 95% of film coverage and is among the brightest of all M42 mount cameras. You focus with a sharp split image circle smack dab in the middle of your frame.

– It’s a tiny SLR! As far as SLRs go, this guy is only 5.3 x 3.6 x 2.1 inches, comparable to a rangefinder. It weighs about 450 grams – to Americans, that’s about a pound or so.

– Very fast maximum shutter speed at 1/2000th – which works completely without any battery power whatsoever!

– It has no hot shoe for flashes or other accessories. It does have a tripod thread. It does have a PC connection for flashes, so you’re not shooting dark. The pleasntly whirry mechanical self timer snaps after 10 seconds.

– The black Bessaflex is compatible with Cosina-Voigtländer’s own side grip and rapid winder accessories. Both fit Nikon DK-16 viewfinder eyecups.

Samples

Here are some sample photos from the Bessaflex TM I took walking around San Francisco. Note that it’s really not representative of the camera in any way since the image quality depends entirely on the film and lens used, but hey.

Conclusion

If you are interested in using M42 lenses or have an existing collection of M42 glass, enjoy the manual process of shooting film with a lack of autofocus and aperture priority (automatic exposure time based on measured light), the Bessaflex may very well be the best camera you can buy.

If you’d like to acquire a Bessaflex TM, there is little hope outside of manual focus camera forum classifieds, local camera shops’ used sections and eBay. It’s extremely difficult to find them new, but hey: it’d be silly to buy one in a box anyway. Cameras are meant to be used, and to acquire one with some history from a user that loved and took care of it is better than one that has been neglected in a box since its manufacturing date. Mine has a few small usage dings on the pentaprism housing at the top, which nobody notices; it works beautifully.

Bessaflex TMs retail for a few hundred dollars more than their original listing price due to their scarcity; the silver one featured in this article typically being a bit more rare and pricier than the black version (around $100 more on eBay – disclaimer: buying through my eBay links supports my website a little!). I’d say it’s worth every dollar, though: the Bessaflex has no comparable equal that’s still being manufactured, and if you enjoy the true experience of photography – the act of taking a photo, rather than the results – why waste your life with anything less than a great camera?

Comments are closed.